How did you discover you wanted to work in branding and get started in the field? Over the years, I’ve worked across product development in strategy, research and design. How you evaluate a design, what you count as data and every action you take are interpretable through the lens of strategic objectives. As an anthropologist, I realized that strategic objectives are fundamentally downstream of—and find their meaning from—positionality, intentionality and purpose. None of these can be understood without reference to culture.

It was very obvious that the distinction between brand and marketing on one hand and product development on the other is entirely artificial. The narratives we tell, symbols we use, artifacts we make, technologies we develop and language we use all cohere more or less by the logic of culture. So, branding isn’t a veneer you put on what you’d otherwise do. It instead represents a mediating hermeneutic that renders intelligible what you do and why. To me, that’s where to find the interesting problems to solve, the position wherein we ask who we are, what we are doing here and why.

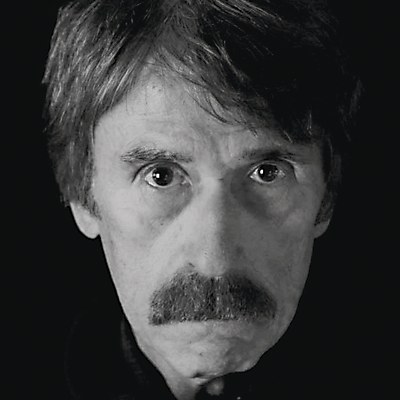

What do you do in your position as senior vice president at global creative and cultural consultancy Space Doctors, and how does your background in anthropology inform your approach? Right now I do a little bit of everything. My primary role is to establish our office in North America, which includes building a team, building relationships, developing our mission and making a difference with each project. The easy part of it all is that we have one of the best support systems in the world: the Space Doctors team itself. It’s why I joined the firm.

There are so many ways anthropology informs my approach and work—most obviously through the practices of observation, critical interrogation, and passion for evidence and culture, among other things. In my case, I think it’s the deep interest in those longstanding theoretical concerns of anthropology reflected in so many everyday problems that keeps me constantly inspired. Topics like personhood, tensions between universalism and particularism, structure and agency, interpretation—all of these classic concerns are refreshed and challenges renewed in the mundane daily questions.

Looking at Space Doctors’s body of work, I love the way that most of your projects expand possibilities for brands, such as examining heat and energy usage for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy or a wider understanding of sexuality for Durex. How do you come up with these ideas? The seeds for ideas are everywhere around us. It’s about getting the right team together with the right expertise in interpreting culture, working closely with our clients and partners, and the ideas start to ignite between us all. More specifically, when we approach cultural analysis, we triangulate diverse signals and look more broadly than the immediate problem. We interrogate cultural phenomena and meaning in broad and adjacent senses so that we can start to see what meanings are old hat, which are dominant and which emerge at the leading edges of cultural production. This gives us an indication of where cultural change is happening and where it’s headed. That can inspire new ideas, provide new perspectives on old problems or even challenge deeply held assumptions.

When working with brands, you pull data from a broad range of sources, including semiotics, cultural and social analytics, AI, ethnography, design trends, and consumer research. What would you say is the benefit of this approach? We’re methodologically agnostic in the sense that we will create the right program for the problem. Sometimes this is a simple discourse analysis. Sometimes it’s a multistage program leveraging trend analysis, AI, ethnography and semiotics. And sometimes it’s an iterative cycle of collaborative workshops and strategic consulting. In any case, a culture-first perspective is foundational and consistent. Culture is what gives meaning to everything that comes after it; it’s the material out of which our desires, motivations, understandings and beliefs are made. Without understanding that, it’s like studying fish without ever mentioning water. So, when we apply research gleaned from data analytics or AI-assisted discourse analysis, we do so in direct collaboration with humanistic, qualitative expertise. It’s the only way to make sense and put into context what we’re seeing.

Tell me what you think of the phrase “human-centered design.” How do you see this concept as being limiting, and why do you think now is the time for designers to reexamine it? It’s certainly come under its fair share of scrutiny lately. Taking each part separately, it’s easy to interrogate the human part: what it means to be human, who is included or excluded, and where it implies that exceptionalism doesn’t exist, among other things. And there are a lot of folks doing that work now. But I think we can agree that in a colloquial sense, to make something more human is to pause and challenge path dependencies, reductive logics, unexamined assumptions and the like. It can represent a genuine desire for more humane development. One way it is ultimately limiting, in my view, is the ways in which it gets operationalized in design practice, whether through types of representations, portability of insights or even methods of engagement. If we turn our attention to the centered part, this too is being challenged. Ecological perspectives, transitional perspectives, critique of anthropocentrism, xenodesign, cybernetic and systems perspectives each problematize the central position of the human relative to the broader interconnected systems people participate in. There’s no shortage of discourse to be found there. And finally, design entails entire worlds of critique from discussions of power and inequality to examinations of growth, consumption and environment. These are all necessary conversations, though a few of them share some of the same questionable premises as their object of critique.

On this topic, one area of my own interest pertains to the cladistic relationship human-centered design and its many critiques have in respect to a particularly western modernity, including individualist, secular and emancipatory liberal subjectivity. Each of these aspects of human-centered design is currently under some form of investigation. To offer what I hope is a productive provocation, I think it’s worth substituting the word center for middle to suggest that humans exist in medias res: suspended between the immanent particularism of the situated local and contingent and the universal—timeless and transcendent meaning.

Philosopher Eric Voegelin borrows the term metaxy from Plato to describe this fundamental human condition of “being in between.” From this lens, to make something more human could be less about how we represent humans—about pain points, desires and design as a therapeutic exercise with humans at the center—and instead be more about appreciating the diverse and ever-expanding plural means by which our cultural expressions are reflections, interpretations and histories of this condition. Value isn’t unlocked through the proliferation of conveniences, numbing discomfort and cultivating appetites; it’s found in deeply connecting with all that gives life meaning and with doing what actually matters.

Importantly, I ask for an appreciation of how we too are actors in this drama. For designers to examine what it means to be human, setting aside human-centeredness—and the critique of human-centeredness that merely dehumanizes and decenters—and instead turn toward what is more human than either: Participation in making meaning. Being more human with all that entails.

Why will a more culturally considered approach better serve both designers and their clients? What can designers do to develop these considerations? In practical terms, the answer is easy. Without a nuanced cultural perspective—both of your audience but also of yourself and the community and context wherein you reside—you run the risk of being irrelevant, incomprehensible or even harmful. None of these are good for business. For designers, every decision you make is a culturally significant one: everything from what you communicate formally to how you even define what a problem is. Using culture as a starting point not only helps you understand what matters but helps you understand and anticipate what will matter. To better develop these considerations, I recommend revisiting and embracing social sciences and cultural analysis. There’s little in the classical analysis of capitalism that isn’t directly applicable to AI today—there’s a wealth of information on animism, personhood, kinship and nonhuman social relationships directly pertinent to today’s questions about identity, belonging, aging and technology. As a complement, I recommend really honing your own work. The discipline, sensitivity, cultural awareness and embodied knowledge that develops through deep participation in a community of practice and in the material engagement of making in priceless.

How is AI and its integration into our everyday technology helping or hurting the brands you work for? It’s certainly helping the brands we work for who are the developers of the AI, except perhaps keeping their teams busy and tired. In all seriousness, their problems are similar to other brands. It’s a bit early to tell, but the single greatest challenge is in determining the nature of the game to be played at the next level up. There are obvious questions about how AI will affect human behavior—and by extension, audiences. There are questions about their own internal processes and their ability to compete. But above these, I think, are questions about the definition of the problem space and the identity of the brand itself. You may have to ask yourself? What is your business now in this new context? Failure to come to terms with this will devastate some brands; those who quickly understand the emerging cultural context will be well poised to make the most out of it and thrive. We’re working on a paper now regarding the replacement, augmenting and transformative possibilities of AI. My recommendation to brands concerned about AI and their future would be to think twice before defaulting to standard consumer research methods and solving today’s pain points and instead start trying to come to terms with cultural change, identifying what the emerging context will look like, assessing who they themselves intend to be and who their audience is. From there, new problems and opportunities will emerge, ones that might have nothing to do with what you see and hear today.

What skills do you think young creatives need to succeed in design and advertising today? I think the most important skill today is the ability to assess and understand the purpose, meaning and objectives of what you’re doing, for whom you’re doing it and on whose behalf you’re doing it. So much time can be wasted in the weeds of production, through force of habit and prioritizing the wrong thing. When planning your work, you can’t underestimate context setting. In terms of skills, despite the world moving faster and faster, I recommend practice, attentiveness, observation and intentionality. You ultimately move faster and smarter if you take your time upfront. If you’re a researcher or designer, this means starting to think in terms of objectives before activities, of goals before methods. Too many times I see junior, mid-career, and even senior designers and researchers applying cargo-cult logic to their workflows—or worse, moving fast and breaking things they never understood to begin with.

What’s the best advice you’ve been given in your career? Be careful not to prejudge what’s relevant.

I’ll surely get the details wrong, but you’ll get the gist. I had an art history professor, Dr. Charles Bergengren, who told a story about a project he was stuck on. He was a folklorist writing about 18th century portraiture. His analysis was stalled because his hypothesis—I forget now what it was—wasn’t informed one way or another by the data he’d collected. Try as he might, he had nothing to say about these portraits that hadn’t been articulated better before. Frustrated and about to give up, he decided to step away and immerse himself in landscape architecture as a means to get outside—and also hoping to never return to these portraits. Of course, in doing so, something unlocked: a “eureka” moment. Something he’d discovered in his exploration of landscape architecture had sparked an insight about his portraits that was new, novel and interesting. The tragedy is that I can’t remember for the life of me what the insight actually was. But the story stuck with me, and to this day, I don’t miss an opportunity to trust the value of observant digression. ca